EXCLUSION

Immediately after Pearl Harbor, the common reaction towards Japanese was one of suspicion and fear, and that manifested in the exclusion of Japanese from aspects of daily life. This included ownership of property, procurement of certain licenses, and even employment with State government.

Alien Land Laws

The right to own property was long forbidden for resident aliens. In 1913, California passed the Alien Land Laws prohibiting aliens—foreign born individuals—who were residents of the state from owning or leasing agricultural property. In 1920, these laws were expanded, closing loopholes and requiring trustees to file annual reports to the Secretary of State.

The panic surrounding the events of Pearl Harbor ignited an investigation into Alien Land Law violations, and so these reports became an avenue for locating Japanese within the state. According to a letter from then-Attorney General Earl Warren, counties were requested to provide information about the location of Japanese. In one letter, Warren admits that what was originally an investigation into Alien Land Law violations became defense planning efforts.

Licenses

Property ownership was just one way in which the State excluded the Japanese from daily life. Japanese were also excluded from purchasing licenses such as liquor, agricultural, or commercial fishing licenses. In some cases, if Japanese already held these licenses, the licenses were revoked.

Agricultural Licenses

C. J. Carey, Chief of the Bureau of Market Enforcement within the Department of Agriculture, barred the issuance of licenses to Japanese. His January 28, 142 letter indicates some of the attitudes towards Japanese.

Liquor Licenses

During this period, the Board of Equalization revoked liquor licenses belonging to any Japanese. The Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control records provide documentation of AB 1582 (1951), the action to reinstate licenses which were revoked during the incarceration. This bill, introduced by Assemblyman Thomas A. Maloney, authorized the reinstatement of liquor licenses to those Japanese from whom licenses were revoked.

After exclusion was rescinded, a court case was filed by T. Taketa, whose license was revoked due to exclusion. In the First District Court of Appeals Case No. 14691, Taketa v. State Board of Equalization, Mr. Taketa sued for wrongful revocation of his liquor license on the grounds of discrimination. His case was unsuccessful due to statute of limitations.

Fishing Licenses

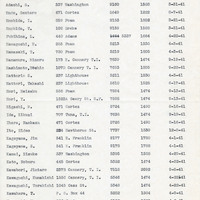

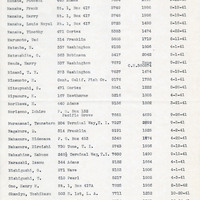

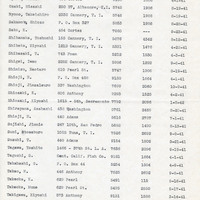

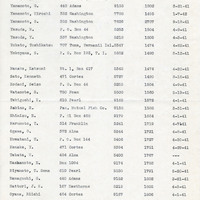

Japanese who possessed commercial fishing licenses were suspected of sabotage. It was feared they might be aware of boating schedules in the harbor and might use that information to harm the State’s war efforts. Lieutenant Commander R. E. Lawrence, Naval Intelligence of the 12th Naval District, requested information on Japanese in possession of commercial fishing licenses in the San Francisco area. A list of names of Japanese in possession of commercial fishing licenses was compiled by the Department of Natural Resources.

State Employees

State employees of Japanese ancestry were also suspect, like in the case of the State Personnel Board. For fear that State records would be used against the United States, pre-emptive action was taken by the State Personnel Board to remove the presumed risk of Japanese from State employment.

The State Personnel Board issued a resolution on March 5, 1942, terminating the employment of people of Japanese descent. The resolution also includes a list of the 14 employees of the State Personnel Board that were fired.