Stories of Service: California's Black Physicians

Records at the California State Archives that were created by the Dept. of Consumer Affairs’ Board of Medical Examiners include many fascinating physicians’ biographies. Known as deceased physicians files, these records include many photographs and newspaper clippings dating back to the first decade of the twentieth century. These files open a window into the lives of Black medical doctors, both men and women, who served their communities and continue to inspire people today.

Dr. S. Sirporah Turner, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Dr. S. Sirporah Turner was a prominent physician in Los Angeles. She was born circa 1889 in Galveston, Texas and attended Bishop College in Marshall, Texas. After graduating with honors from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee in 1907, Dr. Turner became the first female doctor to practice in Shreveport, Louisiana. She opened the Turner Infirmary and Maternity Home in the heart of Shreveport’s African-American community. The clinic specialized in women’s health and maternity care/obstetrics. In addition to tending to her patients, Dr. Turner oversaw the training of student nurses along with her mother, Delilah Robinson, who was a nurse. She relocated to California around the year 1919. At that time, there were only about 3,000 Black medical doctors in the United States. Dr. Turner was married to Ulysses "Slow Kid" Thompson (1888–1990), the famous comedian, singer and dancer. According to her published obituary, she was only 47 years old when she died of cancer on June 19, 1936.

Dr. Frederick Roscoe Whiteman, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F3265, California State Archives.

Another Black doctor who practiced medicine in Los Angeles was Dr. Frederick Roscoe Whiteman. He was born in Memphis, Tennessee around 1893. His father was a physician and his mother was a teacher. There were very few medical schools for African Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some included Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, Howard Medical School in Washington, DC and Leonard Medical School at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. Very few white medical schools would accept Black students. Some that did include the University of Illinois, Harvard University, the University of Michigan, the University of Southern California, Columbia University, the University of Vermont, the University of Pennsylvania and Northwestern University. Whiteman attended Northwestern University and graduated from Meharry Medical College. Dr. Whiteman's newspaper obituary states that he came to Los Angeles in 1923 and died in 1953 at the age of 60.

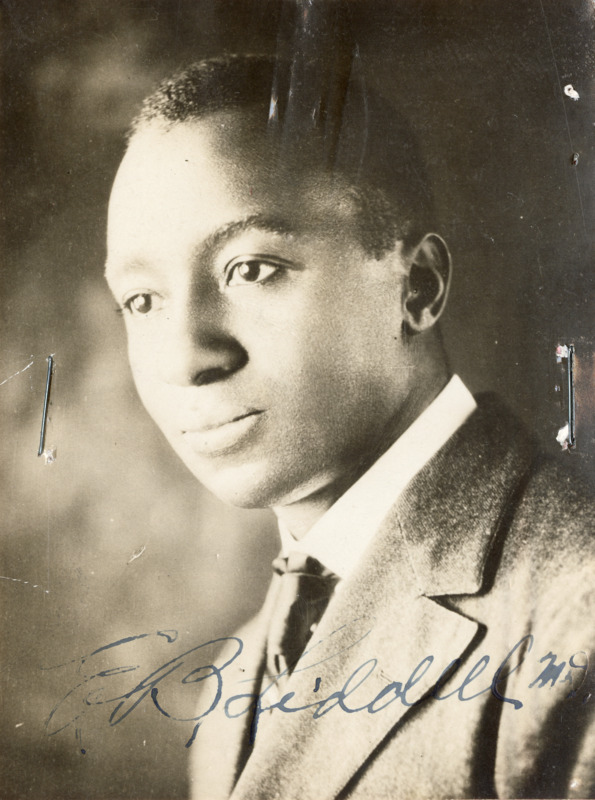

Dr. Elbert Beecher Liddell, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F3265, California State Archives.

Millions of African-Americans left the American South beginning in the early 20th century during what historians call the Great Migration. Many relocated to the Northeast, Midwest, and West, including California, looking for improved living conditions. One of them was Dr. Elbert Beecher Liddell, who was born in Greenwood, Mississippi in 1882. Dr. Liddell graduated from Alcorn State College in Mississippi and Leonard Medical School at Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina. He practiced medicine in South Carolina before moving to Los Angeles in 1923. Dr. Liddell died in 1950 according to his published obituary.

Dr. Francis M. Nelson, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F3265, California State Archives.

One Black doctor who relocated to Northern California rather than Southern California was Dr. Francis M. Nelson. A native of New Orleans, Louisiana, Dr. Nelson was born around 1879 and graduated from Flint-Goodrich Medical College in that city. He was a physician and surgeon in Berkeley, and belonged to both the California Medical Association and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Dr. Nelson's newspaper obituary states that he practiced medicine in the Bay Area for 23 years before his death in 1950 at the age of 71.

Dr. Shelby Louise Boynton Robinson, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F3265, California State Archives.

Dr. Shelby Louise Boynton Robinson, a native of Atlanta, Georgia, practiced medicine in Los Angeles for 22 years. A graduate of Meharry Medical College, Dr. Robinson worked as a physician in Atlanta and Kansas City, Missouri, until she came to California in 1931. She was a member of the American Medical Association, the National Medical Association and the Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority. Her son James A. Robinson, Jr., was a Los Angeles General Hospital-trained supervisor of a hospital in Palestine. Her published obituary states that she died in 1953.

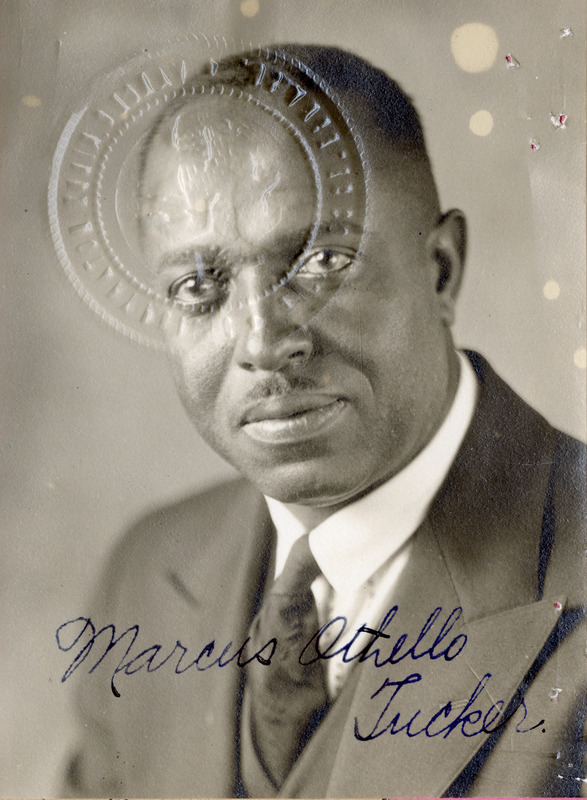

Dr. Marcus Othello Tucker, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Dr. Marcus O. Tucker moved to Santa Monica in 1931, the same year that Dr. Shelby Robinson arrived in Los Angeles. He was born circa 1896 in Dalton, Missouri. This well-known physician attended the University of Kansas and graduated from Meharry Medical College. Dr. Tucker worked at the Santa Monica Hospital, the Culver City Hospital and St. John’s Hospital, and was a member of the American Medical Association and the Los Angeles County Medical Association. Dr. Tucker's newspaper obituary states that he died in 1944 at the age of 48.

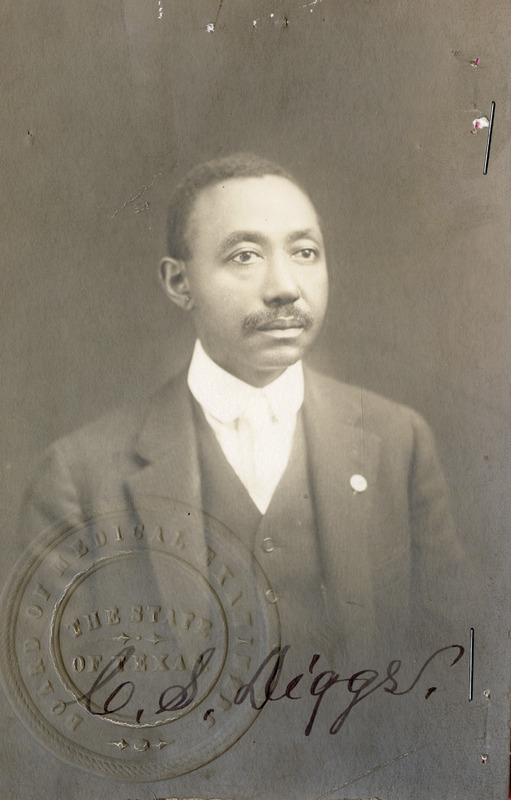

Dr. Charles S. Diggs, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Dr. Charles S. Diggs was one of the first African-Americans to found a hospital in California. In 1924 Dr. Diggs and another Black physician, Dr. Richard S. Whittaker, opened the 20-bed Dunbar Hospital, which was the first, minority-owned, private hospital in Los Angeles. Dr. Diggs was born circa 1879 in Mississippi, and was educated at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (where he played on the football team), Meharry Medical College, and the University of Chicago. He came to California around 1919 and died in 1939 at the age of 60, according to his published obituary. His son, Charles S. Diggs, Jr. was also a medical doctor in Chicago.

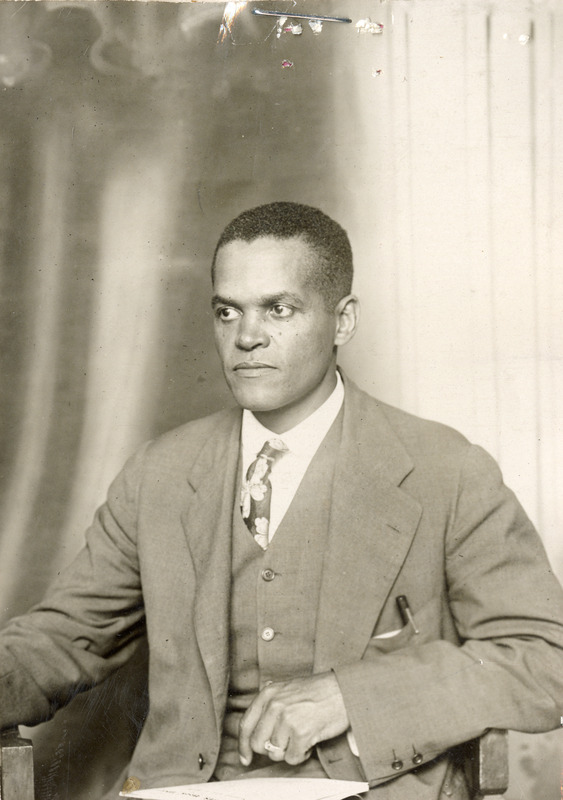

Dr. James Thomas Whittaker, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Dr. Richard S. Whittaker, co-founder of Los Angeles’s Dunbar Hospital, was the brother of the noted physician Dr. James Thomas Whittaker. J.T. Whittaker was born in 1876 and graduated from Louisville National Medical College in 1898. In 1904 he won election as the county coroner in Montgomery County, Kansas, and later served as an army medical officer during the Spanish American War. J.T. Whittaker worked as a doctor in Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma City, Havana, Cuba and in the Philippines before moving to Pasadena in 1917. He volunteered for service in the U.S. Army’s Medical Reserve Corps in that year and was commissioned as a First Lieutenant. Four million Americans served in the First World War, including 400,000 African-Americans. Dr. Whittaker trained at the Medical Officers Training Camp (MOTC) at Fort Des Moines in Iowa, but was honorably discharged in June 1918 having been deemed “not physically capable of performing field service at the present time” shortly before his unit was sent to France. In addition to being a specialist in pulmonary diseases who cared for victims during the Influenza Epidemic, Dr. Whittaker founded the Citizens Cooperative Council in 1929 “to protect the rights and best interests of the Negroes of Pasadena.” This organization lobbied city officials to end city restrictions involving race. Dr. Whittaker’s newspaper obituary states that he died on March 3, 1931. According to the 2016 book African American Doctors of World War I, Dr. Whittaker’s death certificate was signed by his fellow MOTC graduate and friend Dr. Frank A. Pearl.

Dr. Frank Adrian Pearl, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Dr. Frank Adrian Pearl was one of 104 Black doctors to volunteer as US Army medical officers during the First World War. Dr. Pearl, whose brother was also a physician, was born in 1886 in Atchison, Kansas and grew up in Butte, Montana. He studied at the Topeka Vocational Institute and Butte Business College, and graduated with honors from Howard Medical School in 1912. Commissioned as a First Lieutenant in 1917, Dr. Pearl served with the 368th Ambulance Company of the 92nd Infantry Division. The US Army was racially segregated at the time, and the 92nd Division, nicknamed the "Buffalo Soldiers Division," was composed of Black combat troops lead mostly by white officers. Two hundred thousand African-American soldiers served in France and about 40,000 of these men, including Dr. Pearl, saw active combat.

In 1918 the Buffalo Division saw action in eastern France in the trenches of the St. Dié sector of the Vosges Mountains. A German counterattack was successfully repelled at Frapelle. The division suffered over 300 casualties later that year during Meuse–Argonne offensive, which was the deadliest campaign in the history of the US Army. Dr. Pearl’s ambulance company evacuated and treated wounded and sick soldiers to army hospitals. He also innovated new methods in handling injured soldiers that helped surgeons avoid amputations and was promoted to Captain. Discharged after the war, Dr. Pearl moved to Los Angeles and opened a medical office. Not only was Dr. Pearl a member of the American Medical Association, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, the American Legion and the California National Guard, but in 1942 he also served on a special committee to celebrate the launch of the SS Booker T. Washington, which was the first liberty ship to be named for an African American. He also served as the head of the Office of National Defense’s National Disaster Relief Committee in Los Angeles. Dr. Pearl's newspaper obituary states that he died at the age of 62 in 1948.

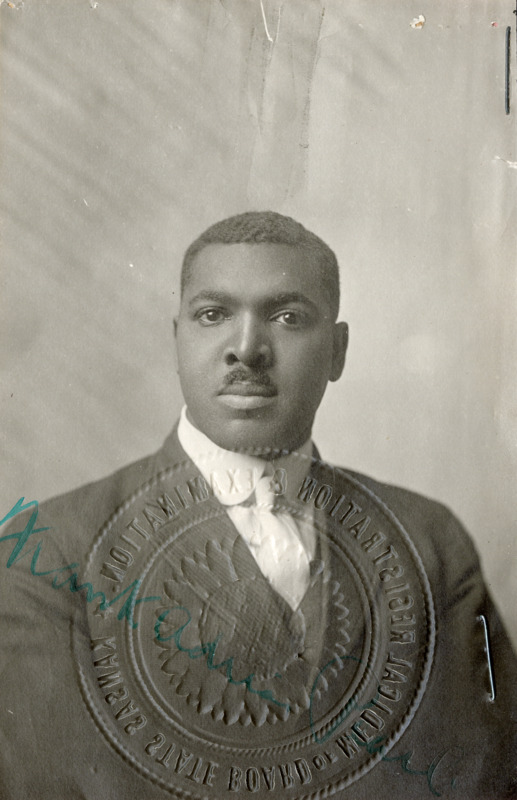

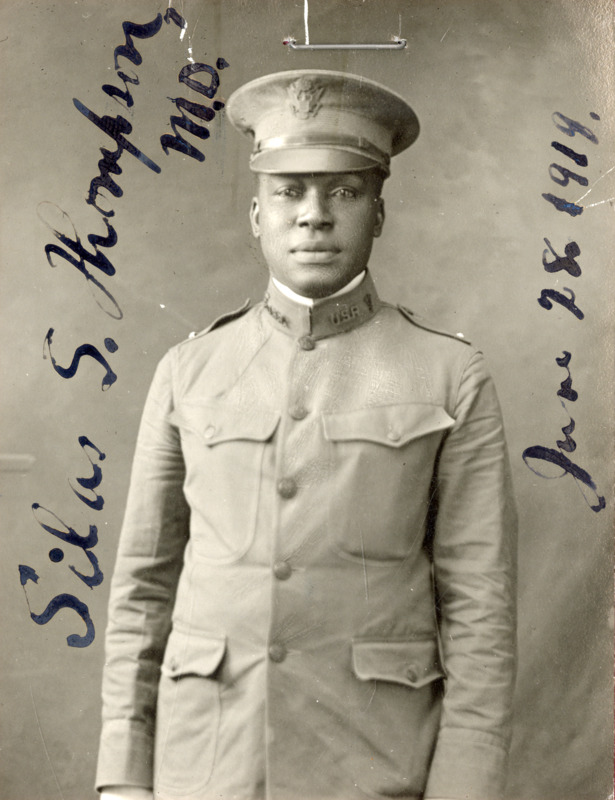

Dr. Silas Stewart Thompson, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F1808, California State Archives.

Another veteran of the Buffalo Division was Dr. Silas Stewart Thompson. Dr. Thompson was born in South Carolina in 1881 and worked as a schoolteacher in Florida. After he graduated from Howard Medical School in 1904, Dr. Thompson was a physician at the Freedmen’s Hospital in Washington, DC. He was deployed to France in June 1918 after being commissioned a First Lieutenant in the U.S. Army Medical Reserve Corps. Dr. Thompson served as a medical officer in 167th Field Artillery Brigade of the 92nd Division. At the time of the armistice, 250 men of the Buffalo Division had died and about 1,200 had been wounded. Dr. Thompson arrived in California after the war in 1919 to practice medicine. According to the 2016 book African American Doctors of World War I, Dr. Thompson died in 1926 and is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Dr. Leonard Stovall, M.D., Deceased Physicians Files, Selected Archives, Board of Medical Examiners, Dept. of Consumer Affairs Records, F3265, California State Archives.

Dr. Leonard Stovall was also a veteran and humanitarian. His family was from Atlanta, Georgia, where he was born in 1887. After moving to Los Angeles as a child, Stovall earned his medical degree from the University of California in 1912. He paid his way through medical school by raising and selling produce. After volunteering as a medical officer during the First World War, Lieutenant Stovall served in France with the 92nd Division at both Frapelle and in the Meuse–Argonne offensive. Upon being discharged from the army in 1919, Stoval returned to Los Angeles to continue practicing medicine as a tuberculosis specialist. He was also a member of the NAACP and an investor. In 1928 he was one of the driving forces behind the opening of the Hotel Somerville in downtown Los Angeles. Later known as the Dunbar Hotel, this facility offered accommodations to predominantly Black cliental at a time when white-owned hotels frequently denied service to Black customers. In 1934 Dr. Stovall opened the Twenty-eighth Street Health Center, a non-profit health clinic in Los Angeles open to all patients regardless of their ability to pay. The following year he founded the Outdoor Life and Health Association, which ran a tuberculosis sanatorium in Duarte open to patients of all races. Dr. Gerald Stovall and Dr. Yolanda Stovall Brooks, Leonard’s son and daughter, also became physicians and joined their father’s medical practice. New treatments for TB eventually made most tuberculosis sanatoriums redundant. The Outdoor Life and Health Association was renamed the Stovall Foundation and changed its mission to providing low-income housing to hundreds of elderly and disabled persons in Los Angeles. According to his published obituary, Dr. Stovall died in 1956.